How an unemployed teacher is changing public education

Kids and communities are responding to seeds of hope planted in the concrete jungle.

Originally published on Fast Company.

By Stephen Ritz

The Bronx stands apart from New York City’s four other boroughs in stark ways. Home to 1.4 million residents and the nation’s poorest congressional district, it once flourished as fertile farmland. Today, we’re restoring this land—not to its agricultural roots, but as fertile ground for raising healthy, happy, and prosperous children.

And in the process, we’re cultivating opportunity for a new generation of citizens.

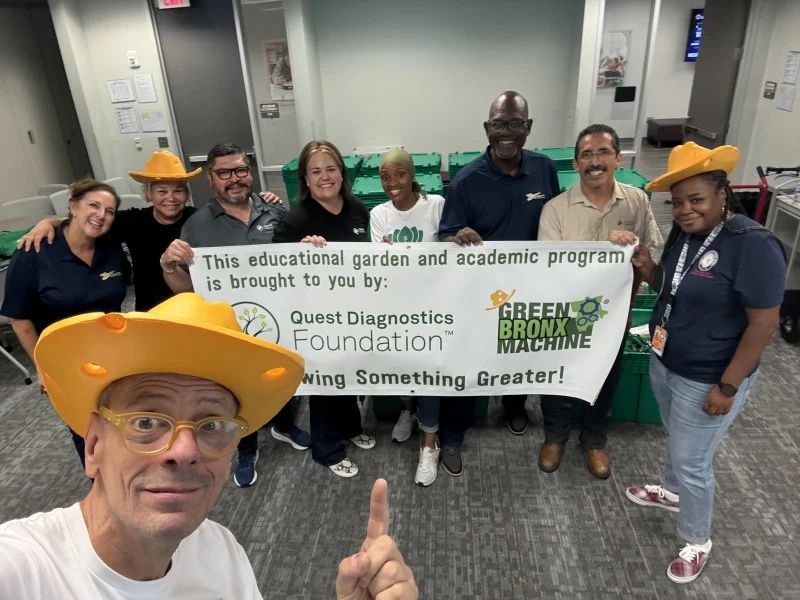

My wife Lizette and I founded and run Green Bronx Machine (GBM). Our nonprofit is dedicated to rewriting the narrative about the Bronx and its residents. Inside Community School 55, just across the tracks from rows of dilapidated public housing towers, sits an unexpected oasis: a thriving garden where fruits and vegetables grow alongside young dreams and possibilities. All year long, grandmothers find respite in the greenery while children eagerly plant seeds, harvest crops, raise chickens, and gather eggs.

But this transformation didn’t begin outdoors—it started in a classroom.

AN “UNEMPLOYED” TEACHER

I playfully call myself an “unemployed teacher.” An educator/administrator since 1984, I left formal employment determined to launch a program that has now spread to more than 1,000 schools across the United States and a dozen countries—with ambitious plans to scale that impact. Dubbed “A Miracle in the Bronx,” we combine urban agriculture, project-based learning, and community engagement that transforms educational outcomes in areas where success seems improbable, if not impossible.

GBM’s classroom model began almost by accident. When struggling to engage my students, I received a box of daffodil bulbs. Instead of discarding them, I tucked them behind a radiator. Weeks later, the bulbs sprouted and bloomed, and with them, a change in students’ engagement and attendance.

These kids, who wouldn’t come to school to see me, were suddenly showing up to see plants. That was my a-ha moment. We planted 25,000 bulbs all across NYC that year.

Today, the program features indoor Tower Gardens and Babylon Micro-Farms, where students grow vegetables year-round in classroom settings, along the way learning math, English, biology, even phys. ed. The results extend far beyond agriculture. Participants show improved academic performance, higher attendance rates, better nutritional habits, and increased environmental awareness. Teachers are similarly inspired and engaged.

Meanwhile, the produce students grow is sold to provide much-needed jobs and income, or taken home by students to feed their families.

I learned that when a child plants a seed and nurtures that plant to harvest, they never go hungry again—not intellectually, emotionally, or physically.

THE VISION DEFICIT IN AMERICAN SCHOOLS

It is common to think that America’s educational challenges stem primarily from limited funding. But the more fundamental issue is a clear vision of what’s possible in today’s schools—something increasingly scarce in an environment dominated by misinformation, politics, and eroding social cohesion.

For children growing up today, the harsh reality is that in America, despite our cherished narrative of meritocracy and individualism, one’s ZIP code remains the primary determinant of social, educational, and health outcomes. That’s exemplified in marginalized areas like the South Bronx.

This geographical determinism is driven by many things. That includes schools in low-income areas being starved for funding, experienced teachers, and enrichment opportunities. Students also face additional barriers such as food insecurity, housing instability, and exposure to environmental hazards—all impacting their ability to learn effectively.

END ZIP CODE DESTINY

By transforming schools into centers of community wellness, individual excellence, and environmental stewardship, we’ve demonstrated that innovative approaches can overcome systemic barriers.

We’re growing high performing schools, engaged citizens, responsible neighbors, vibrant communities, jobs, and we’re growing healthy food—all together.

The program has driven impact across a wide variety of communities, national and international, and that impact is captured in a documentary, Generation Growth, which highlights the program’s success and led to GBM being named a 2024 Most Innovative Company by Fast Company.

SCALE A TRANSFERABLE MODEL

What makes GBM’s method so impactful is its transferability across states and international borders. Schools in diverse settings, from rural Alabama to suburban Colorado, have successfully adapted it to local needs while maintaining core principles. We’re projected to impact 30,000 schools in the United States by 2030.

This isn’t just about the Bronx. There is a Bronx in every American city and around the world; we’ve built a turn-key program that serves all of them. This is about transforming how we think about education, community, sustainability, poverty, and progress everywhere.

Many think I have a larger-than-life personality, but you don’t need that to be effective. It’s about community engagement. Ana Christina Garcia of Sloan Kettering and a GBM board member notes that “Green Bronx Machine capitalizes on community assets and unlocks the potential, desire, and passion that children, principals, and teachers already have. Community engagement is about making organizational resources more accessible to unlock people’s existing talents and power. It’s a two-way street where everyone benefits from sharing their wonderful talents as human beings and creating stronger community connections.” I call this social vitamins fortified with human capacity.

We’re not just growing plants, we’re growing hope. And hope is the most powerful seed we can plant. In 2026 I’d like to shake hands with other thought leaders to continue bringing this proven program across the country. It takes a village, of course, but it also takes an inspiring vision. Join me please.

The author thanks Joel Makower and Jeff Senne for their contributions to this article.